Seals around Palmer Station - part I:

There are two types of seals in Antarctica: most of them are true seals (also called earless seals - note: they do have ears, but they are not visible) and there is only one species of eared seal in Antarctica (more about eared seals later).

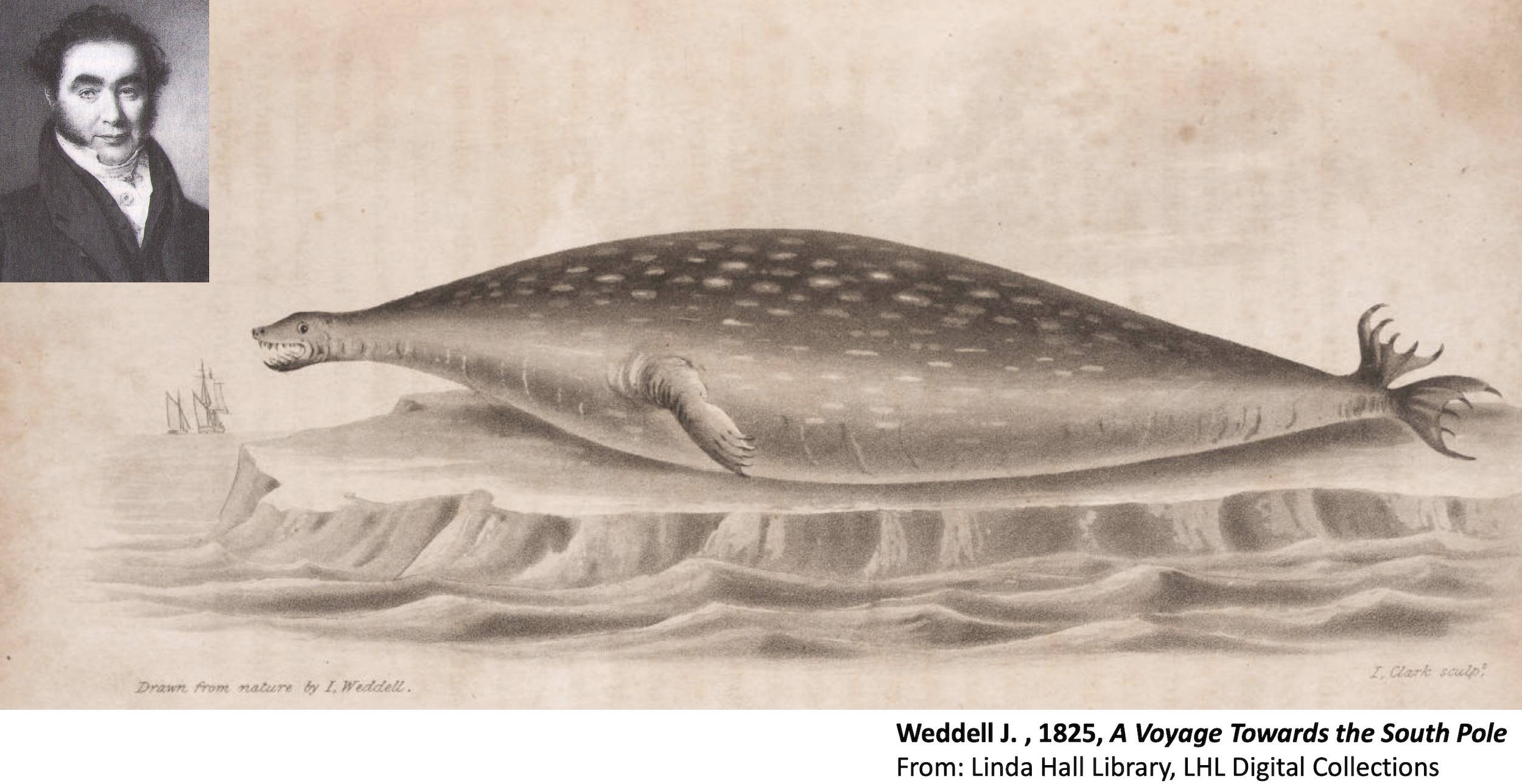

Today I feature the Weddell seal, a true seal. The Weddell seal is the most southerly mammal. They can be found all around the Antarctic continent. They do not venture far out into sea - rather, they stay near shore or ice. They are distinct from other seals because they have a spotted coat and a small head relative to their body size (see exaggerated drawing below from 1825). They can be 10-11 feet long and weigh about half a metric ton (500 kg).

In contrast to other Antarctic seals, it prefers fast ice, and not pack ice. Fast ice means that the ice is “fastened” to land or a stranded iceberg, and therefore does not move with the ocean currents. The Weddell seal is the best studied seal in Antarctica because it is abundant, docile, and does not shy away from humans.

Weddell seals were first discovered by the British sealer James Weddell in the 1820s. News of good sealing grounds in the Southern Ocean led to many sealers exploring more land, including James Weddell and Nathaniel Palmer. The search for seal rookeries resulted in the discovery of the Antarctic Peninsula (in 1820 by Nathaniel Palmer) and the Weddell Sea (in 1823 by James Weddell).

Their main food is fish (e.g., Antarctic cod and silverfish), crustaceans and cephalopods (e.g., squid). They are good divers, going 200-400 meters to hunt. As they may hunt below the sea ice, they are also very adept at finding airholes through the ice. They have excellent memory, because they are able to return to the same airhole after traveling several kilometers away. They certainly are pretty amazing animals.